a high pitched inspiratory sound that indicates a partial upper airway obstruction is called:

Pediatrics Diagram | Quizlet

Pediatrics Diagram | QuizletNo resultsNo resultsProcessing results.... StridorBackgroundStridor is an abnormal and high temperature sound produced by turbulent airflow through a partially obstructed airway at the level of supraglotis, glottis, subglotis or trachea. [] Its tonal characteristics are extremely variable (i.e. hard, musical or respiratory); however, when combined with the phase, volume, duration, apparition rate and associated symptoms, the tonal characteristics of sound can provide additional diagnostic clues. In all cases, the stridor must be differentiated from sterer, which is a lower snoring sound generated at the level of nasofaringe, oropharynx and occasionally supraglotis. Stridor is a symptom, not a diagnosis or a disease, and the underlying cause must be determined. It can be inspiring (more common), maturity or biphasic, depending on its time in the respiratory cycle, and the three forms each suggest different causes, as follows: In most cases of stridor, in addition to a complete history and physical examination, together with other possible additional studies, flexible or rigid endoscopy is required for an adequate evaluation of etiology. Patophysiology The gases produce equal pressure in all directions; however, when a gas moves in a linear direction, it produces pressure in the front vector and decreases the lateral pressure. When the air passes through a narrow flexible airway in a child, the lateral pressure that keeps the airway open can fall precipitately (principle Bernoulli) and make the tube shut. This process obstructs the flow of air and produces stridor. Stridor may result from injuries that affect the central nervous system (CNS), the cardiovascular system, the gastrointestinal tract (GI) or the respiratory tract. EtiologyAgute stridor Laryngotracheobronchitis, commonly known as , is the most common cause of acute stridor in children 6 months to 2 years old. The patient has a bark cough that is worse at night and may have low-grade fever. [, ] is common in 1-2-year-olds. Usually, foreign bodies are foods (e.g. nuts, hot dogs, popcorn or hard caramels) that are inhaled. A history of cough and drowning may be present that precedes the development of respiratory symptoms. [] It is relatively rare and mainly affects children under the age of 3. This is a secondary infection (mainly due to Staphylococcus aureus) that follows a viral process (commonly chromup or influenza). is a complication of bacterial pharyngitis that is observed in children under 6 years of age. The patient has an abrupt appearance of high fevers, difficulty swallowing, refusal to feed, sore throat, hyperextension of the neck and respiratory difficulty. [] is an infection in the potential space between the upper constrictor muscles and the tonsil. It's common in teenagers and preteens. The patient develops severe throat pain, trismus and problems with ingestion or speech. Spasmodic , also called acute spasmodic laryngitis, occurs more commonly in children aged 1-3 years. The presentation can be identical to that of croup. The allergic reaction (i.e.) occurs within 30 minutes of an adverse exposure. Inspiring thickness and stridor may be accompanied by symptoms (e.g., dysphagia, nasal congestion, spicy eyes, sneezing and wheezing) that indicate the involvement of other organs. is a medical emergency that occurs most commonly in children aged 2 to 7. Clinically, the patient experiences an abrupt start of high fever, sore throat, dysphagia and drooling. Chronic stridor is the most common cause of the inspiring stridor in the neonatal period and early childhood and represents up to 75 per cent of all cases of stridor. [] Stridor can be exacerbated by weeping or feeding. Putting the patient in a prone position with the head up relieves the stridor; a supine position exacerbates the stridor. Laryngomalacia is usually benign and self-limiting and improves as the child reaches the age of 1 year. In cases where a significant obstruction or lack of weight gain is present, surgical or supraglottoplasty correction may be considered if the doctor has observed tight mucous bands that hold epiglotis near the true or redundant vocal cords that exceed arytenoids. [] It should be taken into account that the presentation of laryngomalacia in older children (late-initiated) may differ from congenital laryngomalacia. [] Possible manifestations of late laryngomalacia include obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, exercise-induced stridor and even dysphagia. supraglottoplasty may be an effective treatment option. Patients with can present with inspiring or biphasic stridor. Symptoms can be evident at any time during the first years of life. If symptoms are not present in the neonatal period, this condition may be misdiagnosed as asthma. Congenital subglottitic stenosis occurs when an incomplete channeling of subglotti and crycoid rings causes a narrowing of subglottic lumen. Acquired stenosis is most commonly caused by prolonged intubation (see also ). is probably the second most common cause of stridor in babies. Unilateral vocal cord paralysis may be congenital or secondary to birth or surgical trauma (e.g., from cardiothoracic procedures). Patients with a unilateral vocal cord paralysis present with a weak cry and a biphasic stridor that is stronger when awakened and improved when lying with the affected side down. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis is a more serious entity. Patients usually present aphony and a high-pressure biphasic stridor that can progress to severe respiratory distress. This condition is usually associated with CNS anomalies, such as Arnold-Chiari malformation or increased intracranial pressure. Vocal cord paralysis in babies is usually resolved within 24 months. Laryngeal dyskinesia, exercise-induced laryngomalacia, and the paradoxical movement of the vocal cord are other neuromuscular disorders that can be considered. Laryngeal fabrics are caused by an incomplete recanalization of laryngeal lumen during embryosis. Most (75%) are in the gloritic zone. Babies with laryngeal fabrics have a weak cry and a biphasic stridor. The intervention is recommended in the establishment of significant obstruction and includes cold knife or CO2 laser ablation. [] (See .) Lynx cysts are a less frequent cause of stridor. They are usually found in the supragothic region in the epigotic folds. Patients may have stridor, thick voice or aphony. Cytos can cause airway obstruction if they are very large. (See .) Literary hemangiomas (gloats or subglottics) are rare, and half of them are accompanied by skin hemangiomas on the head and neck. Patients usually present inspiring or biphasic stridor that can worsen as hemangioma increases. Typically, hemangiomas present in the first 3-6 months of life during the proliferative phase and regression for the 12-18 months of age. (See .)Medical or surgical intervention for laryngeal hemangiomas is based on the severity of symptoms. Treatment options consist of oral steroids, intralesional steroids, CO2 laser therapy or potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) laser, and surgical resection. Oral proranolol has proven to be effective medical treatment in the appropriate population (it is contraindicated in children with severe asthma, diabetes or heart disease). [] Laryngeal papillomas occur secondaryly to the vertical transmission of the maternal condylomata or vaginal cells infected with the baby's pharynx or larynx during the birth process. These are mainly treated with surgical excision, with questionable use of cidofovir and interferon in refractory cases. [] There is a high rate of recurrence of the disease, with the need for multiple surgical debridations and a small risk of malignancy (5% of malignant degeneration)., if present in the proximal trachea (extratratratratratratracracy) can be associated with the inspiring stridor. If it is present in the distal trachea (intrathoracic), it is more associated with the victorious noise. Tracheomalacia is caused either by a defect in the cartilage, which results in the loss of the stiffness necessary to keep the lumen tracheal patent, or by an extrinsic compression of the trachea. Proximal trachea stenosis can cause stridor. Tracheal stenosis can be or secondary to extrinsic compression. Congenital stenosis is usually related to complete tracheal rings, characterized by a persistent stridor, and requires surgery based on the severity of the symptom. The most common extrinsic causes of stenosis include vascular rings, slings and a double aortic arch surrounding the trachea and esophagus. Pulmonary artery slings are also associated with complete tracheal rings. External compression can also result in tracheomalacia. Patients are usually present during the first year of life with noisy breathing, intercostal reactions and a prolonged phase of expiration. Stridor in babies and children. Schoem SR, Darrow DH, Eds. Pediatric otolaryngology. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012. 323-52. Geelhoed GC. Croup. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1997 May. 23 (5):370-4. Klassen TP. Croup. A current perspective. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999 Dec. 46 (6):1167-78. . Bent J. Pediatric larynxotracheal obstruction: Current perspectives on the stridor. Laryngoscope. 2006 Jul. 116 (7):1059-70. . Lalakea Ml, Messner AH. Retropharyngeal abscess management in children: current practices. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999 Oct. 121 (4):398-405. . Mancuso RF. Stridor in neonates. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996 Dec. 43 (6):1339-56. Ambrose A, Brigger MT. supraglottoplasty pediatric. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2012. 73:101-4. I mean, GP, Burge SD. Laryngomalacia in the older child: clinical presentations and management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Dec. 22 (6):501-5. Amir M, Youssef T. Congenital glottic web: management and anatomical observation. Clin Respir J. 2010 Oct. 4 (4):202-7. . Denoyelle F, Garabédian EN. Propranololol may become first-line treatment in obstructive subglottic childhood hemangiomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Mar. 142 (3):463-4. . Mikolajczak S, Quante G, Weissenborn S, Wafaisade A, Wieland U, Lüers JC, et al. The impact of cidofovir treatment on viral loads on adult recurrent respiratory papillmatosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Dec. 269 (12):2543-8. . Tan HKK, Holinger LD. How to evaluate and manage the stirrup in children. J Respir Dis. 1994. 15(3):245-260. Pryor MP. Noisy breathing in children: history and presentation have many clues about the cause. Postgraduate Med. 1997 Feb. 101 (2):103-12. . Ayari S, Aubertin G, Girschig H, Van Den Abbeele T, Denoyelle F, Couloignier V, et al. Laryngomalacia management. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2013 Feb. 130 (1):15-21. .Carpes LF, Kozak FK, Leblanc JG, Campbell AI, Human DG, Fandino M, et al. Evaluation of the mobility of the vocal fold before and after cardiothoracic surgery in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011 Jun. 137 (6):571-5. Thompson. Laryngomalacia: factors that influence the severity of diseases and management results. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Dec. 18 (6):564-70. . Khemani RG, Randolph A, Markovitz B. Corticosteroids for the prevention and treatment of post-textubation stridors in newborns, children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jul 8. CD001000. Phillips BA. Corticosteroids in respiratory diseases in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012 Jun 15. 185 (12):1328-9. . Natt RS, Helliwell T, McCormick M. Tracheopathia chondro-osteoplastica... an unusual cause of stridor. J Laryngol Otol. 2009 Sep. 123 (9):1039-41. . Brian E Benson, MD, FACS Vice President, Otolaryngology/Cirugy of the Head and Neck, Chief, Division of Laryngeal Surgery and Voice Disorders, Director, The Voice Center, Medical Center of the Hackensack University; Co-Chief, Division of Head Oncology and the John The Cancerure Center Brian E Benson, MD, FACS is a member of the following medical societies: , , , , , Gold Humanism Honor Society, , New York Laryngological Society, Disclosure: Nothing to reveal. Soly Baredes, MD Professor and Chairman, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School; Director of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University Hospital Soly Baredes, MD is a member of the following medical societies: , , , , , , , , , , , , New York Laryngological Society , , International Society of Bass of Skulls Disclosure: Nothing to reveal. Robert A Schwartz, MD, MPH Professor and Head of Dermatology, Professor of Pathology, Professor of Pediatrics, Professor of Medicine, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School Robert A Schwartz, MD, MPH is a member of the following medical societies: , , , Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, Disclosure: Nothing to reveal. Mary L Windle, PharmD Adctjun Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug ReferenceDisclosure: Nothing to reveal. John E McClay, Associate Professor of Pediatric Otolaryngology, Department of Otolaryngology-Cabeza and Neck Surgery, Dallas Children's Hospital, Southwest Medical Center at the University of Texas John E McClay, MD is a member of the following medical societies: , , , Disclosure: Nothing to reveal. Ravindhra G Elluru, MD, PhD Professor, Wright State University, Boonshoft School of Medicine; Pediatric Otolaryngologist, Department of Otolaryngology, Dayton Children's Hospital Medical Center Ravindhra G Elluru, MD, PhD is a member of the following medical societies: , , , , , , , , , , Disclosure: Nothing to reveal. Orval Brown, director of the Otolaryngology Clinic, professor at the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in DallasOrval Brown, MD is a member of the following medical societies: , , , , , , , and Divulgation: Nothing to reveal. Deandra Clark, MD Consulting Staff, Watson Clinic, LLP Disclosure: Nothing to reveal. Mudra Kumar, MD, MRCP, FAAP Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Course Director, Course 6 MSII, Preclerkship Director, Clinical Integration, Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida College of MedicineMudra Kumar, MD, MRCP, FAAP is a member of the following medical societies: , , and Divulgation: Nothing to reveal. What do you want to print? Find us aboutMembershipWebMD NetworkEditions

Pediatrics Diagram | Quizlet

MASTER Volume 1 Chapter 15- Airway Management and Ventilation Flashcards | Quizlet

Lecture Quiz #4 (02/06/19) AlCO Protocols: Protocol Advanced Airway & ITD/Airway Obstruction. LUNG SOUNDS/Some Misc. Diagram | Quizlet

PDF) Respiratory Sounds: Advances Beyond the Stethoscope

Stridor: Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment & More

Characterisation of upper airway obstructions using wide-band snoring sounds - ScienceDirect

PDF) Upper Airway Obstruction in Children

Characterisation of upper airway obstructions using wide-band snoring sounds - ScienceDirect

DOC) measurement lung sound | avinash ch - Academia.edu

Rudolph's Pediatrics 23rd Edition

Part 9: Pediatric Basic Life Support | Circulation

Rhonchi or Rales? Lung Sounds Made Easy (With Audio)

Notes On Basic Pulmonary

Wheezing in Older Children: Asthma | Thoracic Key

Characterisation of upper airway obstructions using wide-band snoring sounds - ScienceDirect

Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders, Fifth Edition

Stridor: Causes, treatment, and what it sounds like

PDF) Auscultation of the respiratory system

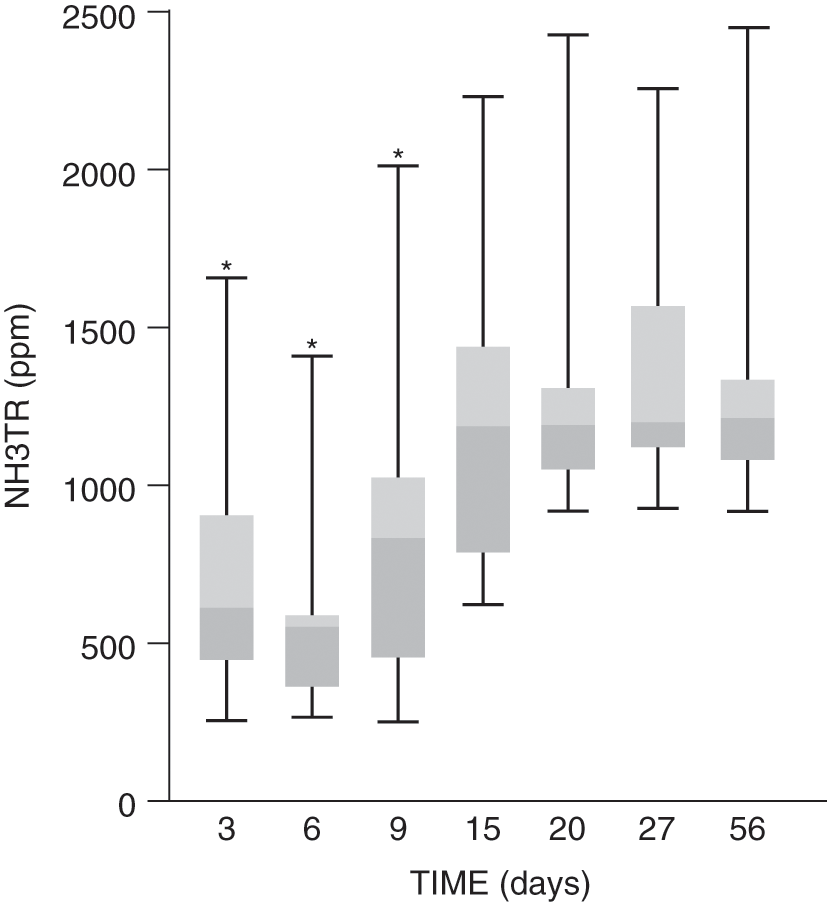

Validation of the Sonomat Against PSG and Quantitative Measurement of Partial Upper Airway Obstruction in Children With Sleep-Di

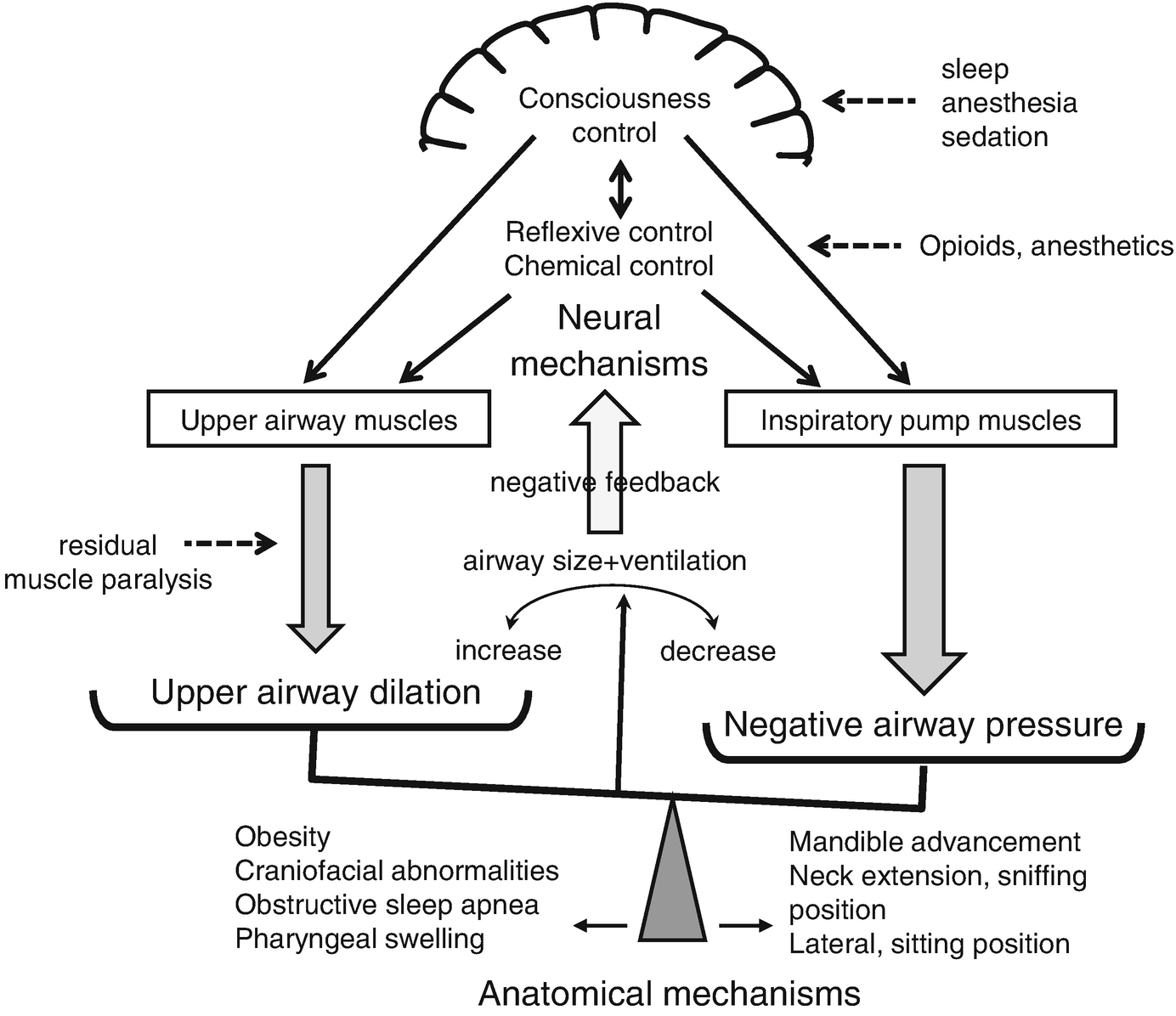

Instability of Upper Airway During Anesthesia and Sedation: How Is Upper Airway Unstable During Anesthesia and Sedation? | SpringerLink

Pediatric Decision-Mdking Strategies to Accompany Nelson Textbook-of Pediatrics, 16th Ed.

SELF-TEST: Respiratory system challenge: Test your knowledge with this quick quiz. | Article | NursingCenter

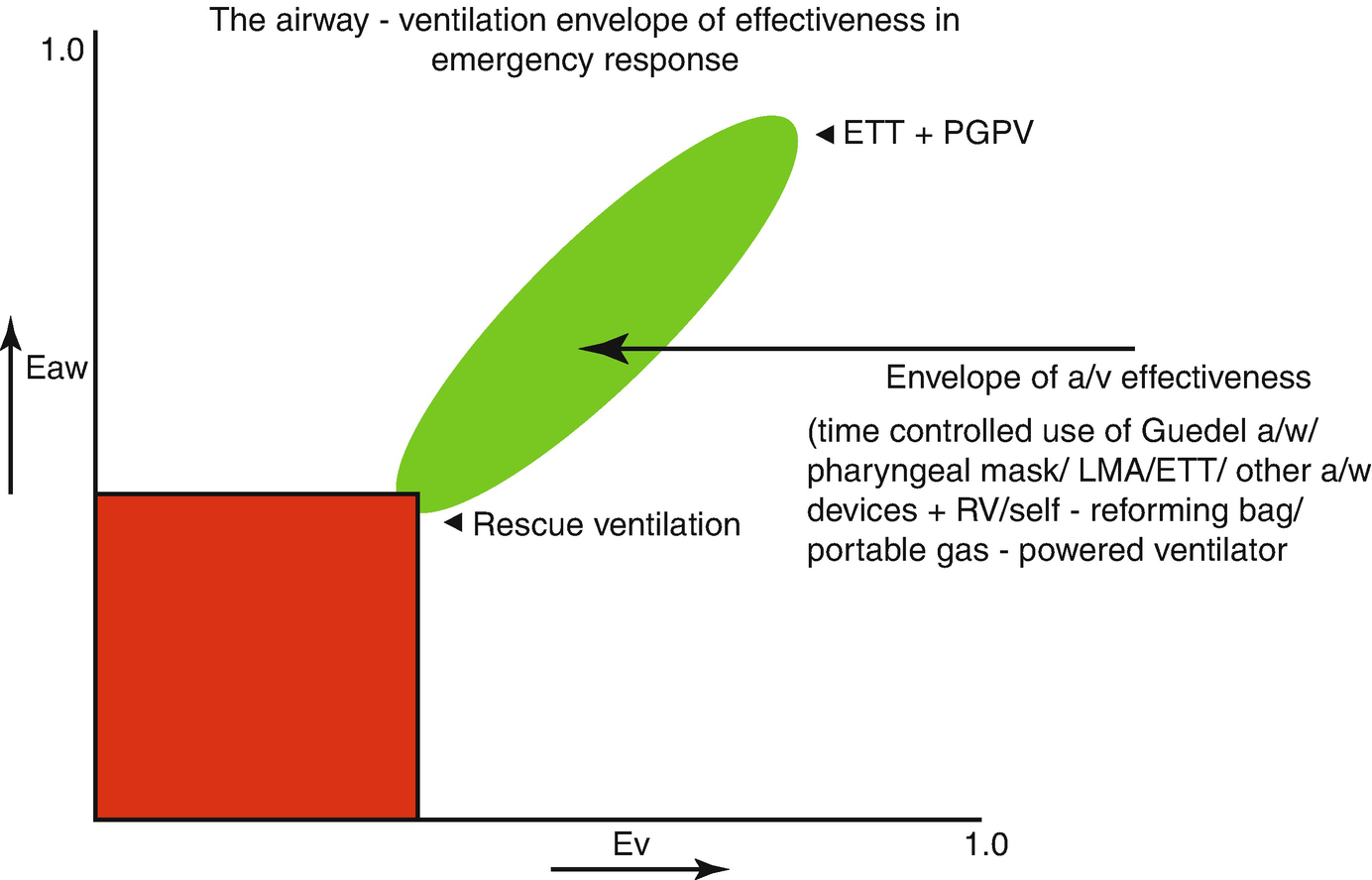

The Management of Respiratory Failure: Airway Management and Manual Methods of Artificial Ventilation | SpringerLink

A normal level of consciousness in an infant or child is characterized by age | Course Hero

Airway management (Chapter 2) - An Introduction to Clinical Emergency Medicine

Airway Management: Background and Techniques (Section 1) - Core Topics in Airway Management

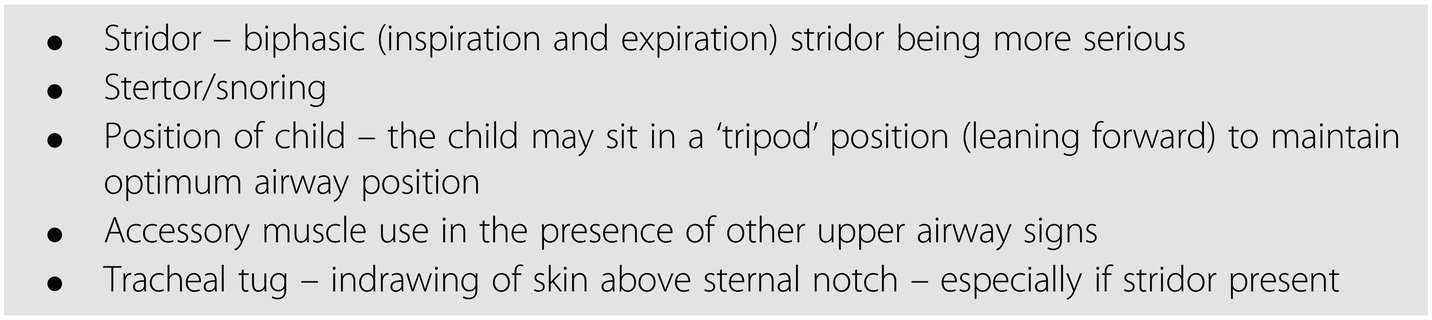

Pediatric Respiratory Distress:

Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders, Fifth Edition

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2007-0078 2007;120;855 Pediatrics Miles Weinberger and Mutasim Abu-Hasan Pseudo-asthma: When Cough, Wheezing,

Stridor: Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment & More

Validation of the Sonomat Against PSG and Quantitative Measurement of Partial Upper Airway Obstruction in Children With Sleep-Di

What's Behind Stridor? Case Studies in Diagnosis and Care | EMS World

Pediatric Decision-Mdking Strategies to Accompany Nelson Textbook-of Pediatrics, 16th Ed.

Stridor: Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment & More

Clinical Conditions (Section 2) - Managing the Critically Ill Child

Validation of the Sonomat Against PSG and Quantitative Measurement of Partial Upper Airway Obstruction in Children With Sleep-Di

Problems in Family Practice Stridor in Childhood

Lung Sounds - Physiopedia

Posting Komentar untuk "a high pitched inspiratory sound that indicates a partial upper airway obstruction is called:"